BRIDGING THE GAP OF KNOWLEDGE AND ACTION: A CASE FOR PARTICIPATORY ACTION RESEARCH

Some researchers could be offended by the following questions: Is all research justifiable in resource poor countries? Is it ethical to do research that is not linked to action?

“Why should I be responsible for action, I am a researcher”, said a colleague. “Is it ethical to curtail my freedom as a researcher?”, she continued.

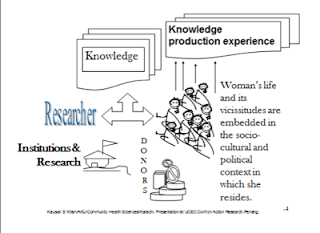

The relationship between knowledge, which research produces, and action which activists love, is not easy to establish. All researchers do not often explore this relationship. Is this because they are driven by the desire ‘to know’? Thus, knowledge acquisition and knowledge production is their priority; ensuring validity of knowledge and considering the rights and interests of the human subjects may be secondary.

Let’s reframe this concern for the relationship between knowledge and action. Let’s concede that some research can be absolved of the challenge to link it to action – example, research in mathematics, chemistry and physics, to name some disciplines. (Oops, even this could be problematic, as use of pure research of physics and mathematics led to the discovery of the atom bomb, and it got used to destroy cities and kills thousands of people. Were those mathematicians and physicists carried a moral responsibility on how their research was used?) BUT, call all research be so absolved of relating knowledge to action? For example, can empirical research around issues of women’s empowerment and subordinate status, be absolved from linking knowledge and action?

Concerns cited above arose as research on women’s empowerment began to be planned by the research team of Community Health Sciences Department of Aga Khan University, Karachi, Pakistan.

The research team decided to ensure that the processes of generating knowledge about factors that impede and facilitate women’s empowerment MUST be linked with action. This was taken as an imperative because the concern was phrased as an ethical concern. It would be unethical, said the team, to gather data for constructing knowledge from women whose rights to shape their lives were constrained because of the social norms, if the women respondents do not get the opportunity to reflect on their own lives and examine the options they have. What choices they made would have to be theirs, and the research team was not to tell them what they should do. The research team was not to be didactic, instead would be facilitative in initiating a thinking and analysis process with the women. What they women would say would be the data of the research. Research thus became the pedagogy for generating action.

Participatory Action Research establishes the link between knowledge and action. It shows how the processes of knowledge production are as important as knowledge as the end-product of the process. It shows that the ‘tools’ used in the process of knowledge making play a critical role. The tools of PRA (participatory reflection and analysis), shaped by the ideology of Paulo Freire make a great difference in the research processes, as they invite the research respondents to reflect and analyze.

The study on women’s empowerment used various PRA tools for facilitating women to be analysts of their lives. This was done in groups, so that the process of such analysis could give women the opportunities for collective actions. Social change, it was assumed, would come from collective action rather than individuals striving for personal gains only (emphasis on ‘only’).

This study on women’s empowerment has raised some issues:

We are interested in your thoughts on these issues and our article! You can access it for the next 30 days by clicking HERE.